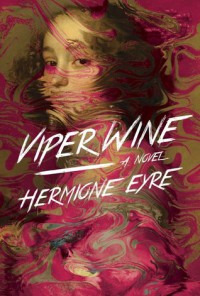

Viper Wine

Historical fiction is perhaps the only genre that I feel iffy about reading – I tend to either enjoy it very much, which is quite rare, or it’s a total disappointment. With “Viper Wine” however I came to accept its numerous shortcomings while at the same time enjoying it immensely, especially because of how far it strayed from the dusk cover blurb. The blurb hypes the book up a bit too much. Magic isn’t really as dominant as it’s made out to be, and the mingling of the 21st century with the 17th is one of the biggest issues with this novel. Yet it has a character of its own. Well-researched and eloquently written it commands the reader’s attention, much like the focal character of Venetia Digby.

There are historical figures which us “common folk” are not informed about, unless they happen to fall under a person’s particular field of study or personal interest. I had absolutely no idea who Sir Kenelm Digby or his wife, Venetia Stanley, were, and it was pleasant to find that historical literature doesn’t just focus on the well-known and slightly over-written figures of Marie Antoinette or Leonardo da Vinci. Despite the fact that this was, ultimately, fiction, the clear evidence of thoughtful research and quotations enhanced the writing quite a bit, particularly one of the chapters near the end which took snippets from a transcript of Sir Digby’s lecture. The prose made it easy to get lost in the world Eyre constructed, albeit it did take some time to develop a kind of flow every time I picked up the book to resume reading.

Venetia’s character was complex and constantly shifted my opinion of her across an imaginary scale, from my strong dislike and even slight hatred for her, to a kind of pitying understanding, to occasional laughter because I could relate to some of her thoughts or reactions. “Viper Wine” is much more than merely a book about a noblewoman’s vanity and desire to preserve her youthful appearance in any way possible. The attentive and thoughtful reader will consider the implications this narrative has, particularly when the (rather poorly done) snippets of the 21st century are considered in the way they violently bleed into the 17th. This is a book about the pressure women face to this day, and the fact that cosmetics and beauty procedures have both gotten safer and more accessible but also more elaborate, dangerous, and pricey. While 30-33, around Venetia’s age in the novel, is no longer the kind of “old maid” marker for women that causes them to fret about growing old and unattractive, this age now fluctuates depending on circumstance and various factors such as social-economic standing. It’s a noel that is also a warning in disguise, skillfully concealed and waiting to be picked up on.

My main irritation with the book was, as mentioned, the way in which it attempted to incorporate an intermingling of centuries, people, and ideas. It was messy, to put it plainly. The scene where Kenelm drops a book and, when he picks it up, discovers that he cannot read it because it’s written in Java, or the presence of historical figures such as Andy Warhol and Mary Shelley which made little sense and served little purpose in the story beyond simply furthering the idea of time constantly bending and interchanging. The influx of scientific terms, procedures, and inventions, such as the frequent mention of the telephone, were easier to forgive because I picked up on what the author was going for about halfway through the book, though I feel it was blunt and sloppy and should’ve been given extra attention and another round of editing for it to be integrated into the novel more seamlessly. Another mild irritation was the subplot of Mary Tree, who goes searching for Kenelm Digby’s aid in order for him to perform the Cure of Sympathy. Yet her subplot receives only a few chapters and is given the most attention near the end, a part of the book where things got rather jumbled and excessive, as if Eyre didn’t know how to finish off the novel, or perhaps didn’t want to, and felt compelled to add at least another 50 pages that were neither here nor there.

“Viper Wine” may not live up to the hype and suspense of its synopsis, but it manages to put forth something much more intriguing and original, and in that sense I was pleasantly surprised. The choppy snippets of modern-day life and the recent past that were included throughout, as well as the 50-70 final pages of the book, came across more as an inattentive fault of the editor who could have easily solved both problems. Putting both of them aside however is easy, as the character of Venetia Stanley is complex and fascinating, worthy of admiration and scorn. She serves as a mother of sorts for the modern woman, and while it was comforting to know that insecurities have plagued women centuries ago it was also terrifying to be reminded just how far the issue has escalated in current society.

1

1